I was thirteen when I first realized that the rest of the English speaking world didn’t talk like me.

Growing up in Everett, a city that borders Boston, the letter “r” was replaced in most words with a throaty “ah” that left the mouth hanging open with every syllable. No matter where you’re from, you’ve likely heard the old phrase, “Pahk ya cah in Hahved yahd” (that’s park your car in Harvard Yard for any of you non-Yankees) exaggerated to exemplify the typical Boston accent.

I remember my moment of shocking realization. I had to stand up in front of my sixth grade class and teach them how to do something. I planned out my whole presentation called, “How to size a ring with no sizer” (it involved the brilliant idea of winding tape around the bottom of the band) and practiced ahead of time by recording my voice with my giant, gray cassette tape recorder. As I played the tape back I froze in horror when I heard myself say, “Then put the ring on your fingah.”

I remember my moment of shocking realization. I had to stand up in front of my sixth grade class and teach them how to do something. I planned out my whole presentation called, “How to size a ring with no sizer” (it involved the brilliant idea of winding tape around the bottom of the band) and practiced ahead of time by recording my voice with my giant, gray cassette tape recorder. As I played the tape back I froze in horror when I heard myself say, “Then put the ring on your fingah.”

My family, my friends, even my teachers all had thick Boston accents. I don’t know why I thought I didn’t, but the recording was enough to make me begin the painstaking and gradual work of eliminating such transgressions as “fingah” from my vernacular.

I listened intently to newscasters with their standard American dialect noting the “correct” pronunciation of words that I hadn’t been able to adjust or figure out on my own. My speech became slower, more deliberate, as I would pause to silently practice words before speaking. My own name was one of the final and most challenging changes to make. The summer before eighth grade I dreaded calling friends and being asked by their parents, “Who’s calling?” In response I’d stumble and choke over my own name. I could say car with ease by then, but for some reason adding an extra syllable sent me gagging out Cahmela in hopeless embarrassment.

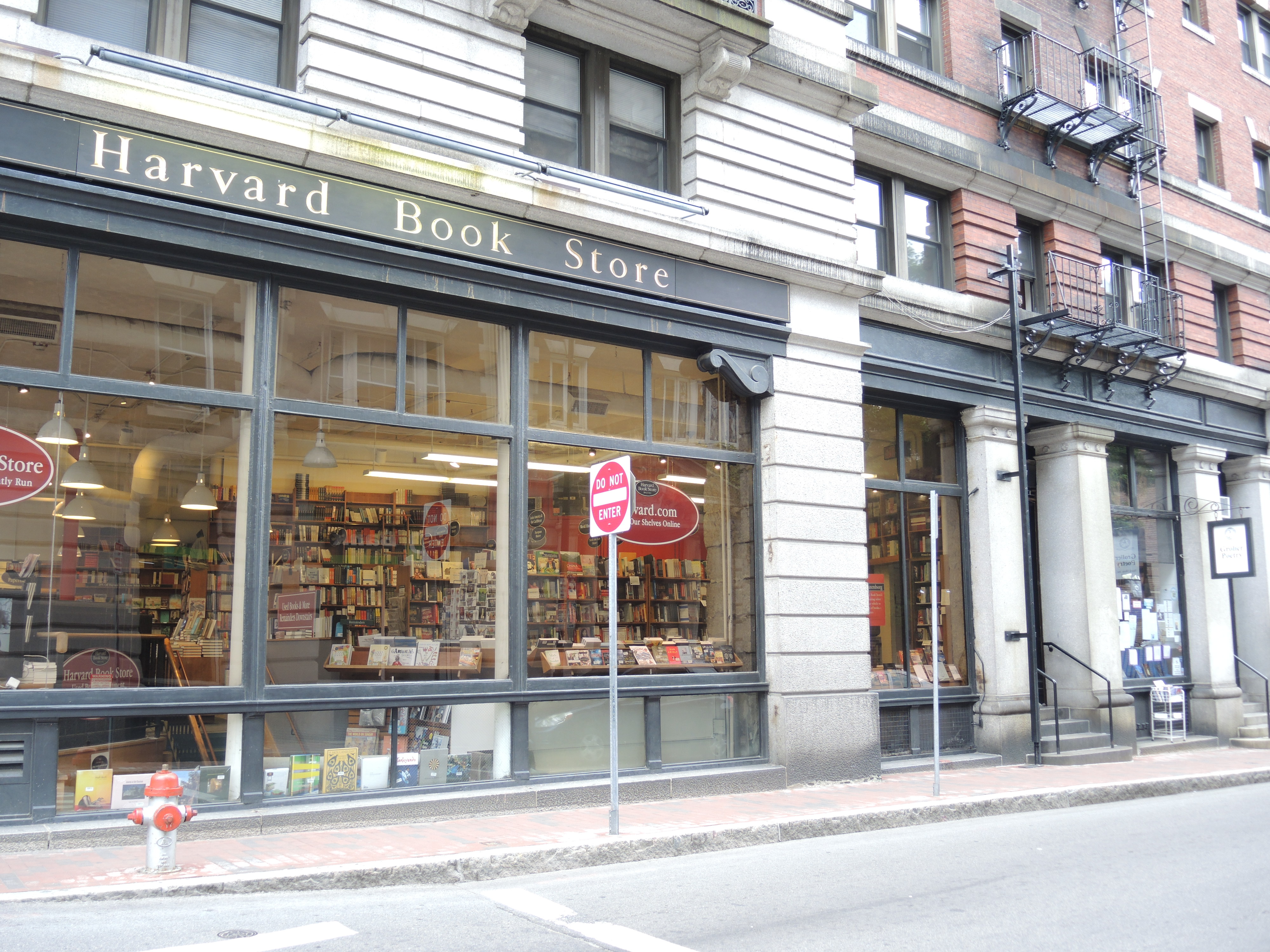

After high school I started working at a bookstore in Boston that attracted tourists from all over. Unable to place my accent, customers were convinced I’d come from somewhere else in the country to attend one of the area’s many colleges. “You don’t sound like you’re from around here,” they’d say incredulously when I explained that I’d grown up in the next town over.

After high school I started working at a bookstore in Boston that attracted tourists from all over. Unable to place my accent, customers were convinced I’d come from somewhere else in the country to attend one of the area’s many colleges. “You don’t sound like you’re from around here,” they’d say incredulously when I explained that I’d grown up in the next town over.

More than a decade later, I’m back to working in a bookstore this time in small town Western North Carolina. Customers look at me, unbelieving, when I admit my roots. “But you don’t have a Boston accent,” they say with quizzical eyes.

My accent was the last thing on my mind yesterday as I dashed out into the pouring rain with a box of books in my arms.

I was headed out to meet a customer at his car since finding parking is a near impossibility in the busy downtown area. He called the store from his cell phone to say he was pulling up in a green beamah in front of the toy store a few doors down

Truth be told, I had no idea what a beamah was although I was more than familiar with the word from the Beenie Man song “Who Am I? (Sim Simma)” that was popular right around the time I was discovering I had an accent. I knew what the color green looked like though, and so I figured that would be enough.

Truth be told, I had no idea what a beamah was although I was more than familiar with the word from the Beenie Man song “Who Am I? (Sim Simma)” that was popular right around the time I was discovering I had an accent. I knew what the color green looked like though, and so I figured that would be enough.

I peered beyond the row of parked cars expecting to see someone double parked, but the street was empty. I started walking briskly along the sidewalk searching for a green car. I walked back and forth three times, then slipped under the green awning of a nearby antique store, glancing down to make sure the hurricane rain that was pouring down hadn’t saturated the box in my arms. My glasses were spotted with rain drops and water dripped from my hair. “No rain jacket?” a man standing under the awning smoking a cigarette said as he eyed me and the box.

“Can you be an extra set of eyes for me?” I said, ignoring his comment. “I’m looking for a green beamah.”

He squinted at me as he blew a stream of smoke from his pursed lips. “What’d you say?” he asked.

“I’m looking for a green beamah. I work in the bookstore there and I’m bringing these books to someone in a green beamah.”

“Where are you from?” the man said gruffly, leaning in to inspect me as if I were an exotic beetle seeking shelter from the rain.

I was growing impatient. Why did this man want to know where I was from? I just needed to find the green beamah, drop off the books, go back to the dry safety of the bookstore.

“Boston,” I said flatly.

“I could tell,” the man said much to my dismay. I decided that he would be of no help and started walking back along the row of cars, but he followed me out into the rain. “There’s a gray BMW right there,” he said pointing. If it weren’t for the rain I would have rolled my eyes upward.

Then out from the bookstore came the man I was trying to meet. In a few quick steps he returned to his car– the gray BMW– and unlocked the door so I could drop the box onto the passenger side seat. The man with the cigarette exchanged a laugh with the customer about my looking for a “beamah.” I didn’t see what was so funny.

Then out from the bookstore came the man I was trying to meet. In a few quick steps he returned to his car– the gray BMW– and unlocked the door so I could drop the box onto the passenger side seat. The man with the cigarette exchanged a laugh with the customer about my looking for a “beamah.” I didn’t see what was so funny.

I went back into the store and began drying my glasses with a paper towel, glad at least to finally know that a beamah was a BMW.

Hours later, my mistake finally hit me. I asked a friend from South Carolina how to pronounce the nickname for a BMW. “Beamer,” he said with emphasis on the er and I blushed as though I’d just slipped a newly sized ring over my fingah.